"Cinderella at 75: How the Princess and Glass Slippers Revived Disney"

Just as Cinderella's dream was set to end at midnight, The Walt Disney Company faced a similar fate in 1947, grappling with a debt of approximately $4 million due to the financial setbacks of Pinocchio, Fantasia, and Bambi, exacerbated by World War II and other factors. However, the beloved princess and her iconic glass slippers played a pivotal role in rescuing Disney from an untimely end to its animation legacy.

As Cinderella celebrates its 75th anniversary of its wide release on March 4, we engaged with several Disney insiders who continue to draw inspiration from this timeless rags-to-riches narrative. This story not only echoes the journey of Walt Disney himself but also rekindled hope within the company and a post-war world yearning for something to believe in once more.

The Right Film at the Right Time --------------------------------To understand the significance of Cinderella, we must revisit Disney's own fairy godmother moment in 1937 with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The film's unprecedented success, holding the title of the highest-grossing film until Gone with the Wind surpassed it two years later, enabled Disney to establish its Burbank studio, still its headquarters today, and paved the way for more feature-length animated films.

Disney's next venture, Pinocchio in 1940, came with a hefty $2.6 million budget, roughly a million more than Snow White, yet it resulted in a $1 million loss despite its critical acclaim and Academy Awards for Best Original Score and Best Original Song. This trend continued with Fantasia and Bambi, further deepening Disney's financial woes. The primary reason for these setbacks was the outbreak of World War II, triggered by Germany's invasion of Poland in September 1939.

"Disney's European markets dried up during the war, and the films weren’t being shown there, so releases like Pinocchio and Bambi did not perform well," explained Eric Goldberg, co-director of Pocahontas and lead animator on Aladdin’s Genie. "The studio was then co-opted by the U.S. government to produce training and propaganda films for the Army and Navy. Throughout the 1940s, Disney shifted to creating Package Films like Make Mine Music, Fun and Fancy Free, and Melody Time. These were excellent projects, but they lacked a cohesive narrative from start to finish."

Package Films were compilations of short cartoons assembled into feature films. Disney produced six such films between Bambi in 1942 and Cinderella in 1950, including Saludos Amigos and The Three Caballeros, which were part of the U.S.'s Good Neighbor Policy aimed at countering Nazi influence in South America. While these films managed to break even and Fun and Fancy Free reduced the studio's debt from $4.2 million to $3 million by 1947, they hindered the studio's ability to produce full-length animated features.

"I wanted to get back into the feature field," Walt Disney reflected in 1956, as quoted in The Animated Man: A Life of Walt Disney by Michael Barrier. "But it was a matter of investment and time. A good cartoon feature requires a lot of time and money. My brother Roy and I had quite a disagreement... It was one of my big upsets... I said we’re going to either go forward, get back in business, or liquidate and sell out."

Facing the possibility of selling his shares and leaving the company, Walt and Roy chose the riskier path, betting everything on their first major animated feature since Bambi. If this gamble failed, it could have spelled the end for Disney's animation studio.

"At this time, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, and Cinderella were all in development, but Cinderella was chosen first due to its similarities to Snow White," said Tori Cranner, Art Collections Manager at Walt Disney Animation Research Library. "Walt recognized that post-war America needed hope and joy. While Pinocchio is a beautiful film, it's not as joyful as Cinderella. The world needed a story of rising from the ashes to something beautiful, and Cinderella was the perfect choice for that moment."

Cinderella and Disney’s Rags to Riches Tale

Walt's connection to Cinderella dates back to 1922 when he created a Cinderella short at Laugh-O-Gram Studios, just before founding Disney with Roy. This short, and later the feature film, were inspired by Charles Perrault’s 1697 version of the tale, which may have originated between 7 BC and AD 23 by the Greek geographer Strabo. It's a classic narrative of good versus evil, true love, and dreams coming true, which deeply resonated with Walt.

"Snow White was a kind and simple little girl who believed in wishing and waiting for her Prince Charming," Walt Disney remarked in footage from Disney’s Cinderella: The Making of a Masterpiece special DVD feature. "Cinderella, on the other hand, was more practical. She believed in dreams but also in taking action. When Prince Charming didn’t come along, she went to the palace to find him."

Cinderella's strength and resilience, despite her mistreatment by her Evil Stepmother and Stepsisters, mirrored Walt's own journey from humble beginnings, marked by numerous failures and challenges, yet driven by an unwavering dream and work ethic.

Walt's vision for Cinderella evolved over the years, initially as a Silly Symphony short in 1933, but the project's scope grew, leading to its transformation into a feature film by 1938. Despite delays due to the war and other factors, the film that emerged was a beloved classic.

"Disney excelled at reimagining these timeless fairytales, infusing them with his unique taste, entertainment sense, heart, and passion," Goldberg noted. "These stories, often grim and cautionary, were transformed into universally appealing narratives, modernizing them for all audiences."

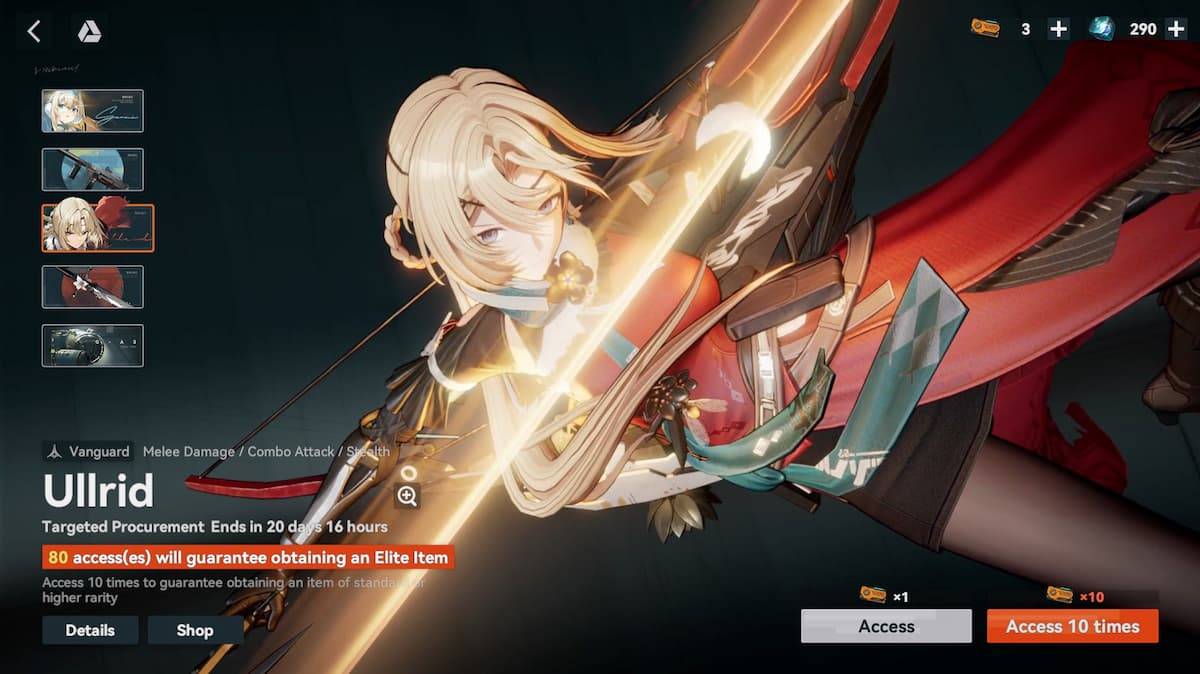

Cinderella's animal friends, including Jaq, Gus, and the birds, provided comic relief and allowed Cinderella to express her true self, while the Fairy Godmother, reimagined as a bumbling grandmother by animator Milt Kahl, added a relatable charm. The iconic transformation scene, where Cinderella's belief in herself and her dreams culminates in a life-changing night, remains a highlight of Disney's legacy.

The animation of Cinderella’s dress transformation, credited as Walt’s favorite, was meticulously crafted by Disney Legends Marc Davis and George Rowley. "Every sparkle was hand-drawn and painted on every frame," Cranner marveled. "There's a perfect moment where the magic holds for a fraction of a second before her dress changes, adding to the scene's enchantment."

The addition of the glass slipper breaking at the end of the film further emphasized Cinderella's agency and strength. "Cinderella is not a cipher; she has a personality and strength," Goldberg emphasized. "When the slipper breaks, she presents the other one she had been holding onto, showcasing her control and resilience."

Cinderella premiered in Boston on February 15, 1950, and had its wide release on March 4, earning $7 million on a $2.2 million budget, making it the sixth-highest grossing film of 1950 and earning three Academy Award nominations. "When Cinderella came out, critics hailed it as a return to form for Walt Disney," Goldberg said. "It was a narrative feature like Snow White, and it revitalized the studio."

75 Years Later, Cinderella’s Magic Lives On

Seventy-five years later, Cinderella's influence continues to resonate within Disney and beyond. Her castle stands as a symbol at Walt Disney World and Tokyo Disneyland, and her legacy is evident in modern Disney films, such as the dress transformation scene in Frozen, animated by Becky Bresee.

The contributions of the Nine Old Men and Mary Blair to Cinderella's distinctive style and character are noteworthy. As Eric Goldberg aptly summarized, "Cinderella's biggest message is hope. It shows that perseverance and strength can lead to dreams coming true, no matter the era."

Latest Articles

![Roblox Forsaken Characters Tier List [UPDATED] (2025)](https://images.dyk8.com/uploads/18/17380116246797f3e8a8a39.jpg)